Tiit Tammaru, editor-in-chief of the Estonian human development report “Estonia at the Age of Migration” writes that Estonia’s three main challenges are in coping with migration dependence, adaptation to multi-nationality and an increase in social cohesion.

The theme of the Estonian human development report 2016/2017 is “Estonia at the Age of Migration”. Social scientists have referred to the 21st century as the migration era, as the number of people living outside of their birth country is greater than ever before. According to data from the United Nations, this number has grown from 190 million in 1990–2015 to 244 million today, 3.3 per cent of the world’s population.

Also, the nature of migration has changed, and its reasons and forms are more manifold than ever before. At the same time, migration has one overarching essential feature – this is the inclination towards welfare. In Estonia, welfare has increased and we have become more attractive to immigrants. Also, the interest of employers in the recruitment of external staff has grown substantially in recent years. What kinds of challenges will the migration era and immigration present to Estonia’s development? In the report, the following most important conclusions on migration and integration have been summarised.

- Estonia’s development has two sides: welfare has increased greatly, but it continues to be unevenly distributed. The growth of welfare measured against the human development index (health, education, wealth) is one of the biggest in Europe within the last 25 years, after Croatia and Ireland. At the same time, inequalities are still significant and also one of the highest in Europe according to the Gini coefficient.

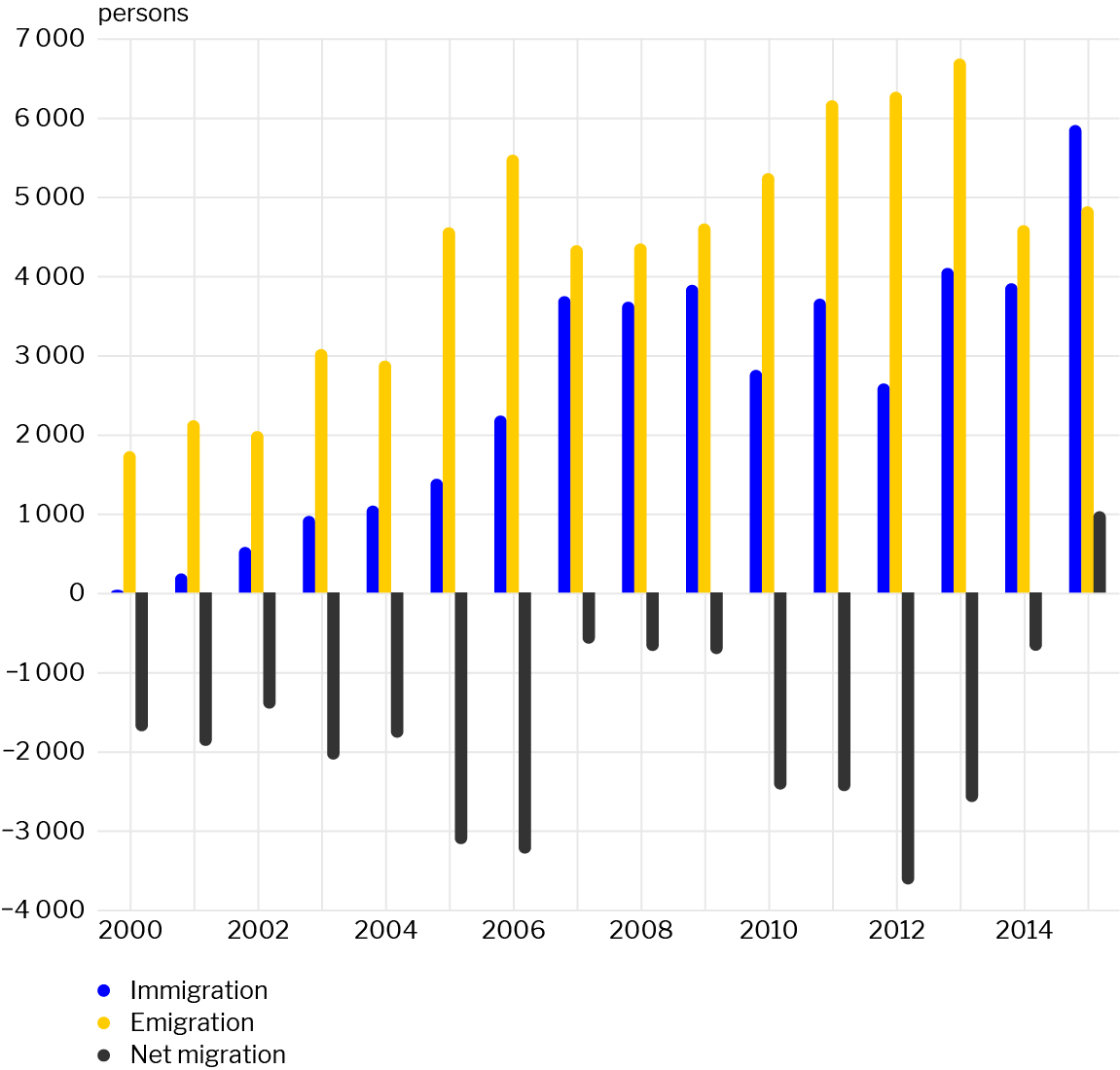

- Migration reverse is taking place in Estonia. The fact that not all of Estonia’s people, especially residents of peripheries and unskilled blue-collar workers, are in receipt of a sufficient portion of the increase in welfare is causing continuous and extensive emigration. With the growth of welfare, immigration has also increased, especially since accession to the European Union (the Figure below the text relates to this result). In 2015, for the first time in the last 25 years, the number of people arriving in Estonia surpassed the number of people departing.

- Estonia’s population will remain at the present level if the birth rate grows and there are more arrivals than exits. We refer to this as migration dependence. In particular, migration dependence can be felt sharply in the labour market, because even if the birth rate increases, the children being born today would only reach the labour market after 25 years.

- The report also reaches the conclusion that the social links between the Estonian-speaking and Russian-speaking communities are still deficient. Common Estonian kindergartens and schools can be triggers of integration with the labour market its promoter, and the success of integration can be measured if people of different nationalities choose and are able to live in the same communities.

- The territories of the states, residential places and commercial spaces do not converge in the open world. The same is true of Estonia where mutually closely communicating communities and people are located in Estonia as well as abroad. Also, many Estonian enterprises have become international, and there are ever more companies that specify their home market as international from the moment of establishing.

Development of many companies depends on immigration and the wellbeing of many people depends on working abroad

- In its twenty-five years of independence, Estonia’s population has decreased by 250,000 people. At least 200,000 Estonians are living abroad who are communicating more or less with their relatives and friends who have remained in Estonia. Approximately 30,000 Estonian residents are working abroad.

- In terms of continuation of the present birth rate, about 440,000 people should immigrate by the end of the 21st century in order to maintain Estonia’s population size.

- Even if a half of these 200,000 Estonians who are living elsewhere in the world would return to Estonia, then the proportion of Estonians may drop lower than at the end of the Soviet era, if the figure is based on immigration alone.

- The continuity of Estonia’s population size in the 21st century at a level comparable to that of today will also be secured by an increase in the birth rate of up to two children per one woman and a positive migration balance of 200,000 people. In this scenario, the number of working-age people would decrease due to the ageing of the Estonian population.

- Estonia’s migration balance turned positive in 2015 due to the arrival of people from outside the EU. Estonia is losing people to other EU countries, but within Europe the nature of migration has changed: there is a significant amount of temporary migration and people maintain close links with their former homeland. We refer to this as multi-nationality.

Therefore, the population of Estonia would not be smaller than the present by the end of the 21st century if the following two conditions would be satisfied: the birth rate would increase and there will be more arrivals than exits. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to contribute to family policy as well as migration policy.

Estonia’s migration policy has already softened significantly, but the decrease in the number of employees is rising year on year, and it is increasingly the wish of employers to recruit labour from outside the EU. At the same time, the activities of our own people and enterprises have become international. The opportunities that accompany multi-nationality are often characterised as “triple victory”: the country of departure (for example, Estonia) will receive work and money for its residents, the country of destination (for example, Finland) will receive a good employee, and the individual will get a better salary and new experience.

Multi-nationality is also expanding our understanding of migration, integration and state. From the viewpoint of the country of departure it is good if people living, studying or working abroad maintain close relations with their homeland, keep the citizenship of their country of departure, establish societies and schools in their countries of destination, follow the media of the country of departure and communicate actively with co-nationals in their homeland.

However, this may become a problem for the accepting country, if strong homeland and community relations are not balanced by integration into the society of the country of destination and people continue to live within the information and media space of their former homeland.

There’s a high probability that Estonia must consider the continuous decrease of its population as well as of employees within the next couple of decades – the latter is boosted by people’s wish to work abroad. In order to avoid a decrease in the number of employees, a much greater amount of immigrants will be needed than Estonian society would be able to integrate.

This means that the labour force problems must be solved by means of different measures, not immigration alone. The movement of companies higher in value chain is important. We also need new and suitable approaches to forming integration, labour market, taxation and social care policies.

Estonia’s integration policy requires reconsideration

- Estonia has become more a country of Estonians within the last 25 years and such a situation differs from most other European countries. The positive migration balance of recent years with countries outside of the EU will gradually increase the proportion of people of other nationalities in Estonia again. The geography of the new immigrants is wide, but they are mostly arriving from Russia and Ukraine.

- The kindergarten and school system that is dividing children continuously into parallel worlds on the basis of the Estonian and Russian languages causes inequality between the residents of Estonia and influences the integration of new immigrants. People arriving from Russia and Ukraine meet their common Russian-language environment in Estonia, incl. Russian-language kindergartens and schools.

- Within the last 25 years, Estonians have progressed quicker to higher career levels than Russian-speaking people. As a result, the income of Estonians is also bigger.

- In virtue of the difference in incomes, Russian-speaking people cannot afford to purchase homes in the same areas as Estonians. In addition, the location of Russian-language kindergartens and schools influences the choice of places of residence Russian-speaking people.

- According to data from PISA, the performance of pupils in Russian-language schools is lower than that of Estonian-language schools. The proportion of people with higher education is smaller within young Russian-speaking people than among Estonians.

The current approach based on language teaching has not increased the coherence of society, and Estonian language skills remain passive within many Russian-speaking people, as life, study and work as communities are defined by language. With a segregated educational system commencing from kindergarten, young people do not have common communication networks or even a common information space.

For example, Russian-language kindergartens and schools have remained closed on the basis of language, very few Estonians go to Russian-speaking kindergartens or schools, and there are also Russian-speaking children in Estonian-speaking kindergartens and schools.

Social cohesion can also be increased by supporting communication between different language groups in addition to attaching importance to the Estonian language. The state can initiate changes most effectively via education. The common Estonian school system cannot emerge simply with the closing of Russian-language schools, as this would raise high tensions. Learning must rely on the Estonian language, but it must consider the linguistic and cultural diversity of the residents of Estonia.

The solution must involve families and communities in addition to education. Fears and conflicts are a natural part of integration. These main fears must be dealt systematically, such as the fear of national conflicts at school, fear of mixing of identities and fears of the parents of Russian children diminishing the performance of schools.

Future

Three important challenges of Estonia’s development for the next couple of decades include coping with migration dependence, adaptation to multi-nationality and an increase in the cohesion of the society.

The population of Estonia will decrease if migration does not come about. The assessment of the integration capacity of the arriving people through recruiting a foreign labour force will mitigate future problems. As a basis for labour migration, an innovative points system should be considered, whereby the capabilities of all persons applying for work in Estonia would be assessed from the viewpoint of the needs of the labour market (spread in the European countries) as well as of integration (spread in North America). People who achieve a sufficient number of points are welcome in Estonia. The consideration of integration capacity would increase the confidence of the Estonian people and would allay the fears related to migration.

The nature of migration has changed within Europe and it is necessary to adjust to multi-nationality, or the situation whereby people are roaming temporarily or are operating simultaneously in several countries. The biggest challenge for countries in relation to multi-nationality would be in cases where territory and citizenry would not coincide.

To whom belong the people living in a multinational world in terms of political, citizenship, taxation or social security? How much property should be owned or taxes paid in a homeland, winter home or country of work to be eligible, for example, to the right to vote? It is necessary to start to deal with these issues systematically.

In order to deal with Estonia’s three challenges of the migration era, coordinated activities are required – migration, multi-nationality and integration policies form an integral whole. Estonia’s previous governments have concentrated on the development of a favourable economic environment, incl. the development of a physical infrastructure, proceeding from the understanding that economy prosperity would also bring happiness to other areas of life.

Economy is very important, but society is a much more multi-layered phenomenon. The main challenge of the governments of 21st century Estonia is to contribute to the development of people. This challenge also concerns schools, communities and companies. Estonian companies are strong if they are well attuned to global supply chains and provide smart working places. The state can offer support to companies and take the lead in changes.

To this end, a well-advised innovation system is required that would contribute to creativity from kindergarten, with the inception of manifold linguistic-cultural baggage that suits the migration era and the acquisition of technological literacy required for the digital era across all sectors of society and nation groups living in Estonia.

You can read the Estonian human development report in full online at www.inimareng.ee